“Why is Russia’s PACE Platform, which is supposed to represent the Russia of the future, populated by its past?”

On 29 January, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe held its first meeting involving the Platform for Dialogue between the PACE and Russian Democratic Forces in Exile.

REM examines how the Platform was created — and why the result has disappointed many.

The opposition’s anti-corruption efforts: Where do we go from here?

Anti-corruption investigations once mobilized protests and reshaped opposition politics in Russia. Today, they seem to land in a political void.

Can investigative activism still matter under conditions of total repression and a full-scale war?

And if so, what form should it take now? Answers Dr. Ilya Matveev.

Read more … The opposition’s anti-corruption efforts: Where do we go from here?

Electoral expert on preparations for Russia’s 2026 State Duma elections

Despite the apparent stagnation of Russia’s political landscape, elections are still held and retain some elements of competition.

The 2026 State Duma campaign has begun, marked by pressure on Yabloko and other parties — and by the growing visibility of war veterans in politics, as discussed in a recent interview.

Read more … Electoral expert on preparations for Russia’s 2026 State Duma elections

Election update XV

As Russia prepares for the State Duma elections, Kremlin is intensifying pressure on systemic opposition.

More on this in our digest covering the main election developments in November-Dezember 2025.

No time for heroes?

Russian propaganda hails returning fighters from Ukraine as a rising new elite, fast-tracked into politics and public roles.

However, most Time of Heroes graduates end up in visible but powerless positions designed to pose no threat to the Kremlin.

According to a new Verstka report, political strategists running the program are even instructed to select candidates who lack the aura of genuine military glory — ensuring they remain politically harmless.

Election update XIV

REM summarizes the outcomes of September elections and examines how opposition is seeking to consolidate its efforts ahead of 2026 State Duma vote.

At the same time, the party landscape continues to shrink, while state pressure on Yabloko intensifies.

Read more in this digest of key electoral developments from September – October 2025.

Operation “Legitimacy”: Inside Russia’s Governor Elections

Leaked documents reveal that this year’s governor re-election campaign in Irkutsk relied on systematic violations of electoral rules.

The scale and structure of the operation suggest that it is not an isolated case, but part of a coordinated model used across Russia’s gubernatorial elections.

Read more … Operation “Legitimacy”: Inside Russia’s Governor Elections

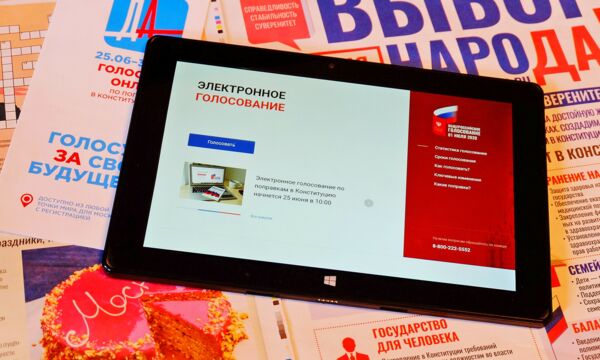

Russian authorities shelve plans for mass rollout of electronic voting

E-voting was expected to be the Kremlin’s key tool for securing favorable outcomes in the 2026 State Duma elections.

Now, sources close to election officials have revealed plans to scale back its use.

What are the reasons behind this possible shift in strategy?

Read more … Russian authorities shelve plans for mass rollout of electronic voting

Experts: High results in 2025 governor elections attributed to vote rigging

Electoral analyst Ivan Shukshin has examined the results from several Russian regions where gubernatorial ‘elections’ took place in September 2025.

His unambiguous conclusion: the results were falsified.

REM publishes some of Shukshin’s conclusions.

Read more … Experts: High results in 2025 governor elections attributed to vote rigging

Statement on Russian regional elections 2025

On 12–14 September 2025, Russia held regional elections.

Elections were held in 81 regions with more than 5,000 election campaigns at various levels.

REM monitored the voting process and summarized the main conclusions from the observation.

Election update XIII

On 12–14 September, Russia will hold regional elections. While these events can hardly be described as genuine elections, they remain one of the few available indicators of internal political dynamics.

In this digest, REM examines the changes to electoral legislation introduced ahead of the vote, as well as the results of candidate registration.

Who is next? Persecution of governors in Russia

On 7 July 2025, former governor of the Kursk region Roman Starovoit was found dead in an apparent suicide, according to investigators.

During Vladimir Putin’s 25-year rule, 32 Russian governors have faced prosecution.

This article explores how the Kremlin’s approach to prosecuting regional elites — both allies and critics — has evolved over Putin's time in power.

Is Siberia retaining its autonomy? Municipal reform and unexpected protests

In spring 2025, Vladimir Putin signed a new law on local self-government.

The reform unexpectedly triggered backlash from regional leaders, deputies, and citizens — especially in Siberia and the Far East — that culminated in a mass rally in Gorno-Altaysk.

REM examines the evolution of local self-government in Russia and explores why seemingly formal administrative changes have sparked such resistance.

Read more … Is Siberia retaining its autonomy? Municipal reform and unexpected protests

Election watchdog ‘Golos’ announced shutdown. Is this the end of independent monitoring?

The announcement was made on 8 July, shortly after Golos co-chair Grigory Melkonyants had been sentenced to five years in prison.

Following this, Golos shuttered regional offices and suspended all ongoing projects.

Read more … Election watchdog ‘Golos’ announced shutdown. Is this the end of independent monitoring?

Election update XII

United Russia primaries mark the beginning of a major electoral cycle that will culminate in the 2026 State Duma elections.

Read more about this in our digest of the main electoral developments in April–May 2025.

Why is Russian government still afraid of elections?

Ahead of 2026 parliamentary elections, Russian authorities are redrawing constituency boundaries.

It seems that after 25 years of undermining the electoral process, the Kremlin should not be concerned about the outcome, yet it is.

Redistricting is part of a broader strategy to manipulate elections, along with other tactics. This article explores how Kremlin has refined these tactics over the years and why they do not always succeed.

Read more … Why is Russian government still afraid of elections?

The verdict on local self-government will be carried out by governors

A new law on local self-government took effect in Russia, significantly altering the structure of local governance.

Originally designed to eliminate the two-tier system, the final version of the law made some concessions, but the end of local self-government as it was known seems inevitable.

Andrey Pertsev analyzes the reform’s early impact.

Read more … The verdict on local self-government will be carried out by governors

A great friendship? Russian propaganda and German elections

Russian “soft power” is a hot topic in both Russian and foreign media.

How effective actually is it? And what are the Kremlin’s fake publications up to in Germany?

Historian Ewgeniy Kasakow, author of the book "The Special Operation and Peace", analyzes the Kremlin’s main strategies and achievements in its fight for a German audience.

Read more … A great friendship? Russian propaganda and German elections

Georgy Filimonov: Authoritarian experiment in Vologda

The governor of Vologda Region has become infamous for his controversial and ideologically driven approach to governance.

A total ban on abortion, a dry law and the erection of a monument to Stalin are just some of Filimonov's initiatives.

In this analysis, REM delves into how Filimonov’s rise reflects a shift in the Kremlin’s broader vision for regional politics.

Read more … Georgy Filimonov: Authoritarian experiment in Vologda

Repression in numbers: Three years of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine

In February 2025, human rights organization OVD-Info published a report documenting key trends in political repression against anti-war activism in Russia.

The report sheds light on statistics of criminal and administrative cases related to anti-war activities over the last three years.

REM publishes an abridged version of the report.

Read more … Repression in numbers: Three years of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine

Election update XI

As Russia prepares for the 2026 State Duma elections, Kremlin dismantles local self-government system.

More on this in our monthly digest covering the main election developments in February - early March 2025.

“Foreign agent” filter for parliamentary opposition

The Russian Ministry of Justice is increasingly labeling members of systemic parties as 'foreign agents' — targeting prominent regional politicians who lose their parliamentary mandates and the ability to participate in elections.

Andrey Pertsev explores how this will change the new composition of the State Duma and the party system.

Read more … “Foreign agent” filter for parliamentary opposition

Report: Critical state of freedom of speech

The Mass Media Defense Centre, Russia's leading human rights organization for media and journalist rights, has released its annual "Freedom of Speech – 2024" report.

With detailed analysis of new laws and statistics on media persecution, the report sheds light on the growing threats to free speech and independent journalism across the country.

REM summarizes the key findings of the report.

Election update X

Russia begins preparations for the Unified Voting Day and State Duma elections 2026.

Read our brief overview of key political trends and major electoral events of early 2025.

National republics against the vertical power structure

Kremlin is preparing a large-scale municipal reform, aiming to abolish tens of thousands of urban and rural settlements across Russia.

The initiative has faced criticism from the leadership of the affluent and populous republics of Tatarstan and Bashkortostan, with State Duma Speaker Volodin effectively sabotaging its adoption.

This article explores why the Kremlin's municipal reform drew criticism from seemingly loyal regional politicians.

Read more … National republics against the vertical power structure

2024: A year of great hopes and crushing disappointments

Looking back at the past year, REM presents a political summary of 2024 in Russia.

More on the key election-related developments and what to watch for in 2025 – in this article.

Read more … 2024: A year of great hopes and crushing disappointments

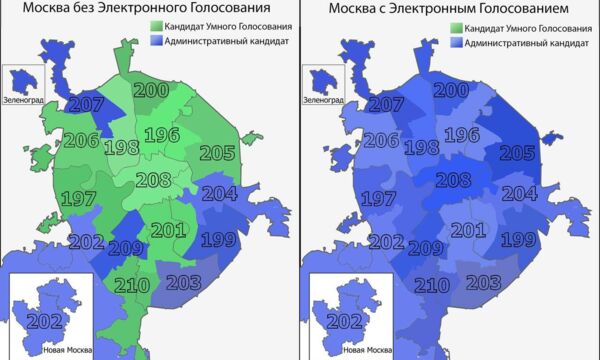

"Big Brother" of Russian elections

Electronic voting is poised to become Kremlin's key tool for securing desired outcomes in the 2026 State Duma elections.

This analysis explores how Kremlin and regional authorities are leveraging e-voting system for their gain ahead of the upcoming parliamentary elections.

“Valuable staff”: How Kremlin is turning war participants into school teachers

Schools in Russia are not only educational institutions but also key players in the electoral process. Most polling stations are located at schools, while school staff make up the majority of election commission members.

To address the shortage of teachers in small towns and villages, Kremlin is now retraining 'war veterans' as educators.

This reportage explains how it works.

Read more … “Valuable staff”: How Kremlin is turning war participants into school teachers

Who funds United Russia?

The wealthiest political party in Russia, which has maintained a dominant position in power for over 20 years, receives annual funds large enough to cover the expenses of a small town.

Sirena project conducted a thorough analysis of the party’s financial report, identifying its key sources of support.

REM summarizes its main findings.

Report: COVID-19 pandemic and war have not altered the funding system of Russian political parties

According to the recent Golos report, the rules meant to ensure financial transparency of political parties are not functioning as intended.

Instead, parties have become more secretive and learned to circumvent legal restrictions.

REM shares key findings of the report.

Trauma of repression: How state persecution of Russian activists alters their lives

1,073 individuals in Russia have been subjected to political repression, with 331 currently in prison.

REM presents an abridged translation of a 7х7 reportage on the trauma of political repression.

Its heroes' personal accounts highlight the reasons behind low political engagement in Russia.

Read more … Trauma of repression: How state persecution of Russian activists alters their lives

Immunity from the military: How Russia's power vertical resists career advancement of the “special military operation” participants

Vladimir Putin often refers to participants in the war as the "true elite".

However, the results of the regional elections show that the system is not ready to place 'frontline soldiers' in key positions, and the military itself is not keen to pursue deputy roles, which are often unpaid.

CPRF: Does the “party of the past” have a future?

What is the Communist Party of the Russian Federation undergoing amidst the war and the totalitarian evolution of Putin’s regime?

Does it stand any chance of surviving Putin? And what can the CPRF’s past reveal about its future?

Journalist Azamat Izmailov traces the party’s evolution.

Read more … CPRF: Does the “party of the past” have a future?

Without respect for fundamental freedoms: Ten reasons why Russian elections and their results cannot be considered democratic

Due to repressions against the observers, reduced number of parties and remote e-voting system, the results of the September elections were contrary to the statutes of international law.

Media monitoring: After the elections

REM commissioned an independent team of analysts to monitor Russia's leading social networks, VKontakte, Odnoklassniki, Telegram and Youtube, to explore how the Kremlin's propaganda machine works on social media using actual data.

We present the main observations below, as well as visualized data and graphs illustrating the findings.

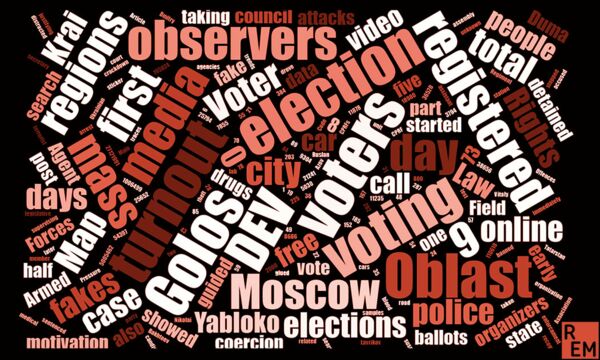

Statement of the Golos movement on the results of the regional elections of 6-8 September 2024

The Movement in Defense of Voters' Rights Golos has published a final statement on the results of the regional elections in Russia in September 2024.

REM presents an abridged English version of the statement.

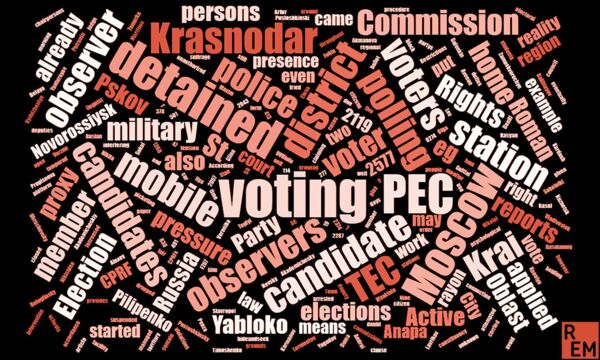

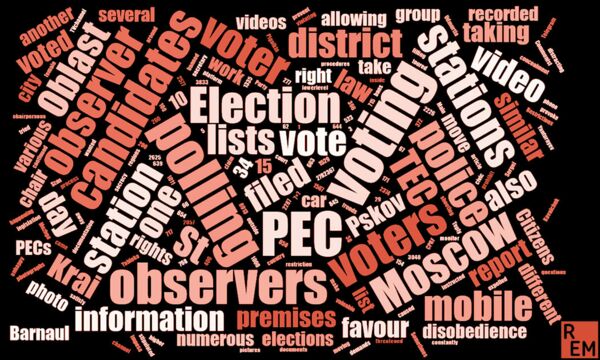

Express review of the third voting day on 8 September

Based on the Golos report, REM summarizes the key trends observed during the third voting day (Unified Election Day) of the regional elections 2024.

Read more … Express review of the third voting day on 8 September

Express review of the second voting day on 7 September

Based on the Golos report, REM summarizes the key trends observed during the second voting day of the regional elections 2024.

Read more … Express review of the second voting day on 7 September

Media monitoring: Before the elections

REM commissioned an independent team of analysts to monitor Russia's leading social networks, VKontakte, Odnoklassniki, Telegram and Youtube, to explore how the Kremlin's propaganda machine works on social media using actual data.

We present the main observations below, as well as visualized data and graphs illustrating the findings.

Express review of the first voting day on 6 September

Based on the Golos report, REM summarizes the key trends observed during the first voting day of the regional elections 2024.

Read more … Express review of the first voting day on 6 September

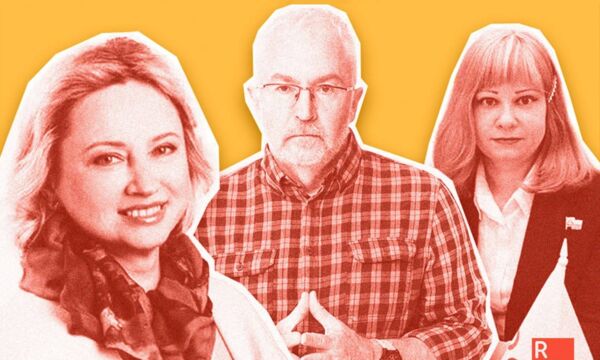

"We don't need a woman, she won't be able to manage our district". How Russian women are running for office

In 6-8 September elections, 83 men and only 12 women are running for governor in 21 regions.

Being a female politician in Russia means facing numerous challenges.

7x7 shares stories of women who stand for office in 2024.

Kaliningrad region: The political landscape before the elections

How has Russia’s invasion of Ukraine affected the situation in the Kaliningrad region? What is the background and what should we expect in the upcoming regional elections?

Journalist and activist Roman Kolevatov answers these questions.

Read more … Kaliningrad region: The political landscape before the elections

The phantom of competition

To let disgruntled voters blow off steam, Kremlin has returned to the theme of "competitive elections" for the first time in many years.

However, in the absence of real competition such strategy may backfire.

Andrey Pertsev explains why Kremlin creates an illusion of contest in predictable elections.

Competitive elections in Russia remain only at the local level

By-elections to the State Duma, elections to regional and local legislatures, as well as elections for heads of municipalities and local councils, will take place in the regions of Russia on 6-8 September 2024.

Observers prepared a final report on the results of candidate nominations and registrations.

REM publishes an executive summary.

Read more … Competitive elections in Russia remain only at the local level

“We will start small”

How can a deputy of a city duma help people?

Why are trade unions so important for Russia?

What will make sanctions a fairer political tool?

Evgeny Stupin, deputy of the Moscow City Duma, was stripped of his deputy's mandate because of his anti-war stance. In this interview, he talks about his achievements and plans.

Beglov — a riddle of Putinism?

Why will the most unpopular governor of Saint Petersburg win the upcoming election? And how is Beglov significant to the Kremlin and to Putin personally?

Political observer Maksim Veselov discusses how “The Beglov Era” in St. Petersburg perfectly encapsulates today’s Russia and why Beglov serves as the role model of Putin’s clerk.

Between extinction and degradation: Do systemic parties have a future?

How did “systemic parties” emerge in Russia?

What makes a political party “systemic” in general? And why does Vladimir Putin’s regime still need them?

Political researcher explores these questions.

Read more … Between extinction and degradation: Do systemic parties have a future?

No region in Russia has a competitive gubernatorial election campaign

The movement in defense of voters' rights Golos has published an analytical report on the results of nomination and registration of gubernatorial candidates.

REM summed up the main takeaways in this article.

Read more … No region in Russia has a competitive gubernatorial election campaign

Who rules Russian regions. Alexander Kynev on how the system of power has changed over 30 years

In his recently published book, Kynev described how regional politics has changed from the collapse of the USSR to the present day: how forces were distributed, how the power vertical was built, and how heads of regions turned into regular managers.

REM publishes a translation of 7x7 interview with him.

The main intrigue of September elections — will Communists regain their positions?

Russian authorities have done everything to make the elections predictable and boring, and voters hardly ever go to them at all.

And yet — should we expect something interesting from the September elections?

REM publishes a translation of the 7x7 interview with expert Alexander Kynev.

Read more … The main intrigue of September elections — will Communists regain their positions?

“I’d really like to live in Russia”

What is the meaning of clandestine electoral campaigns in modern Russia?

Could the experiences of political struggle in other countries be adopted by Russian activists in the future?

Activist and politician Ksenia Bezdenezhnykh on her electoral experience and workplace politics.

A wizard with federal connections

In June, Vladimir Putin appointed Andrey Turchak as the acting head of the Altai Republic, an economically depressive and sparsely populated region.

This appointment was seen as a "punishment" for Turchak's continued good relations with Yevgeny Prigozhin, founder of the Wagner private military company.

Meduza tells how Andrei Turchak is trying to please Altai residents and earn his return to Moscow.

Kremlin plans to reelect Alexander Beglov as governor of St. Petersburg

In September 2024, Vladimir Putin’s hometown will elect its governor. Most likely, it will again be the Kremlin's protégé Alexander Beglov.

Presidential Administration's documents leaked to the journalists of “Vot tak” indicate that the entire campaign is managed from a single center, and Beglov’s rivals are carefully selected candidates with no chance of winning.

“Vot tak” reveals how Kremlin is running a fake campaign that costs 1.8 mln USD.

Read more … Kremlin plans to reelect Alexander Beglov as governor of St. Petersburg

"Admitting helplessness is much scarier than the situation in Russia"

Vladimir Zhilkin is an anti-war candidate for the Moscow City Duma. He is a politician, human rights activist and sociologist from Tambov, a provincial city 500 km from Moscow.

REM publishes an abridged translation of Zhilkin's interview for 7x7, where he talks about his campaign, Muscovites' attitudes towards the war, and why it is important to run for election even when there are no free elections.

Read more … "Admitting helplessness is much scarier than the situation in Russia"

Moscow Mayor's Office decided not to allow opposition candidates to City Duma elections and to conduct the campaign quietly

The Moscow parliament should be ‘maximally cleared’ of opposition candidates, with 'Sobyanin's people' taking their place. The election campaign should not attract unnecessary attention.

According to sources of the Verstka media, these are the objectives set by the Moscow mayor's office for the upcoming elections on 8 September.

“I’m not going to leave my neighborhood”

Gleb Babich's campaign was one of the most remarkable campaigns in this year's Moscow City Duma elections.

On 16 July, Moscow Election Commission declared 8% of signatures collected by Gleb Babich invalid. The left-leaning urban activist will not be registered as a candidate.

In this interview, he talks about the goals and challenges of his campaign as well as the meaning of collective discussion and action in today’s Russia.

Election update IX. Russia begins preparations for Unified Voting Day 2024

In September, elections will be held for 13 regional legislatures and 22 governors.

Kremlin is actively preparing by further restricting both the citizens’s voting rights and political competition in 'problematic' regions.

More about the election-related developments of May/June 2024 in this review.

Read more … Election update IX. Russia begins preparations for Unified Voting Day 2024

'They decide who lives, who gets imprisoned, and who gets elected'. Russia bans 'foreign agents' from elections

Recently the parliament of Georgia, despite widespread public unrest and warnings from the EU, passed a law on 'foreign agents', commonly referred to as 'the Russian law'.

In this article, REM discusses the evolution of the legislation on foreign agents in Russia and the recent legislative amendments on the participation of 'foreign agents' in elections.

"Something's been tweaked somewhere!": Participants in the war in Ukraine ran in Russian elections and failed

Despite being given advantages, only 19 war participants won ‘passable’ parliamentary seats in United Russia primaries.

How was this even possible? Read in the article by Verstka.

When did it all go so horribly wrong? The Russian opposition turns to introspection

The Anti-Corruption Foundation’s latest documentary series with the heavy title Traitors raises complex questions about the 1990s as a myth and as an actual historical period that had consequences for the present - questions about opposition strategy, communication style, political platform and Russia’s possible future.

In this essay, Dr. Ilya Matveev reflects on each of these questions in turn.

Read more … When did it all go so horribly wrong? The Russian opposition turns to introspection

Russian expatriate voting: Generational divides, gender gap and electoral manipulations

How do Russians living abroad vote and what factors drive their electoral behavior?

In the presidential election 2024, volunteers conducted exit poll surveys in 44 countries where Russian citizens cast their votes.

The results identify the most problematic polling places with significant discrepancies between survey results and official voting results.

Read more … Russian expatriate voting: Generational divides, gender gap and electoral manipulations

Parties in a coma

The results of presidential campaign 2024 raise questions about the future of the party system.

For the first time in the post-Soviet history of Russia, none of the parliamentary candidates gained more than 5% of the vote - at least according to the official data.

This means the party machinery for mobilizing core supporters is virtually inoperative.

As Putin enters his fifth term, what transformations is Russian party system going through? An analysis by Riddle.

The new Kadyrov. Who could become the next head of the Chechen Republic?

Although the 47-year-old Chechnya's leader Ramzan Kadyrov denies rumors about his potentially fatal illness, media and experts on Russian elites claim that Kremlin has begun to develop a plan for power transfer.

What kind of person does Kremlin need to be in charge of Chechnya, and who are potential candidates for this post – in REM's review.

Read more … The new Kadyrov. Who could become the next head of the Chechen Republic?

Election update VIII. Preparations for the Unified Election Day 2024 have started

United Russia tries hard to nominate war veterans for regional parliaments, the party system continues to decline, while Chechnya acknowledges the use of coercion to vote in the last presidential elections.

More about the election-related developments of March/April 2024 in this review.

Read more … Election update VIII. Preparations for the Unified Election Day 2024 have started

An undesirable cudgel

In the first three months of 2024, Russian authorities declared more organizations “undesirable” than in the full year of 2022.

The law on undesirable organizations was adopted in 2015. Foreign NGOs labeled “undesirable” are banned from establishing legal entities, disseminating information and implementing programs in Russia.

This long read examines how the legislation on undesirable organizations has evolved since then and how the law is enforced today.

Russian opposition: A strategic impasse

The current state of opposition politics in Russia is paradoxical. Despite commanding considerable resources, the opposition has not had any strategic or even tactical successes for a long time.

In this essay, a political scientist discusses the impasse in which the Russian opposition finds itself and outlines three areas for strategic discussion about its future.

Vote report. How Kremlin uses social media to control and boost turnout

REM commissioned an independent team of analysts to monitor Russia's leading social networks, VKontakte and Telegram, to show how the Kremlin's propaganda machine works on social media.

Here are the results of social media monitoring during the voting days on March 16-18, 2024.

Read more … Vote report. How Kremlin uses social media to control and boost turnout

Electoral anomaly in Cyprus. How Foreign Ministry and CEC fabricated 40,000 votes for Putin

We collected evidence demonstrating why the presidential vote 2024 in Cyprus can be considered the largest overseas electoral fraud in Russia's modern history.

Fire, ink, Noon against Putin: How Russians resisted illegitimate elections

Russia's three-day presidential vote 2024 seemed to be the most non-transparent in its history.

In this article, we provide an overview of the civic resistance at polls during the voting days.

Read more … Fire, ink, Noon against Putin: How Russians resisted illegitimate elections

22 million fake votes for Putin? How Kremlin rigged the election results 2024

Various methods of data analysis can be used to detect electoral fraud.

Several investigative teams counted that at least 22 million votes — a third of the 65 million ballots cast for Vladimir Putin — were cast fraudulently. Keep reading to find out how it works.

Read more … 22 million fake votes for Putin? How Kremlin rigged the election results 2024

Statement on the Russian presidential elections 2024

Based on Golos observers' reports, REM summarizes the three-day presidential vote results and reports on electoral violations.

Read more … Statement on the Russian presidential elections 2024

Express review of the third voting day on 17 March

Based on the Golos report, REM summarizes the key trends observed during the third voting day of the presidential election 2024.

Read more … Express review of the third voting day on 17 March

Express review of the second and beginning of the third voting days on 16-17 March

Based on the Golos report, REM summarizes key trends observed during the second and the beginning of the third voting days of the presidential election 2024.

Read more … Express review of the second and beginning of the third voting days on 16-17 March

Express review of the first voting day on 15 March

Based on the Golos report, REM summarizes the key trends observed during the first voting day of the presidential election 2024.

Read more … Express review of the first voting day on 15 March

Russia uses social media as a major campaigning tool in its presidential elections

REM commissioned an independent team of analysts to monitor Russia's leading social networks, VKontakte and Telegram, to show how the Kremlin's propaganda machine works on social media.

Here we present the main findings, fascinating data, and diagrams revealing the mechanisms behind this massive propaganda machine.

Read more … Russia uses social media as a major campaigning tool in its presidential elections

Election update VII. The campaign results: Russian authorities make the election run dry

In this article, REM summarizes the results of the presidential election campaign 2024, focusing on agitation and administrative mobilization.

The text is based on the respective report published by the election watchdog Golos.

Read more … Election update VII. The campaign results: Russian authorities make the election run dry

How the authorities allure Russians to the election to increase the turnout

In regimes such as Russia's, a typical voter lacks motivation to participate in the elections due to the high predictability of the outcome.

At the same time, election organizers need to ensure a high turnout to show that the society is not tired of its national leader even after decades of his rule.

How do they do it? Find out in this long read.

Read more … How the authorities allure Russians to the election to increase the turnout

Navigating opposition strategies in presidential election 2024

As the presidential vote looms, Russian opposition is trying to develop the most sensible voting strategy.

Although the whole setup is highly orchestrated, three options are on the table. What are they?

Read more … Navigating opposition strategies in presidential election 2024

Who is Vladislav Davankov – a new hope for opposition in the presidential election?

After the CEC refused to register Ekaterina Duntsova and Boris Nadezhdin, it became clear - in presidential election 2024, there will be no one on the ballot who opposes the war in Ukraine and criticizes the government.

Nevertheless, prominent opposition leaders continue to agitate Russians to go to the polls and vote for "anyone but Putin". The most obvious choice for many is Vladislav Davankov, a presidential candidate from the New People party.

Read more … Who is Vladislav Davankov – a new hope for opposition in the presidential election?

In Memoriam: Alexei Navalny (1976 - 2024)

Reflecting on Alexei Navalny's political journey, this text recognizes his substantial impact on Russian elections - for both the past and probably the future.

Navalny played a crucial part in enlightening Russian society about elections through his campaigns, emerging as a symbol of will and hope for the most thoughtful segment of the population.

His legacy leaves an enduring mark on the landscape of Russian politics, which will not disappear with his murder.

Election update VI. Results of presidential elections 2024 candidates registration

Golos, the Movement in defense of voters' rights, has published a report summing up the results of candidates' nomination and registration during the Russian presidential election campaign 2024.

In this review, we share the main takeaways.

Read more … Election update VI. Results of presidential elections 2024 candidates registration

How voter signatures collection turned into an impassable barrier for the opposition

Boris Nadezhdin, an anti-war candidate for the Russian presidency, was not registered as such by the Russian Central Election Commission.

Being nominee of a non-parliamentary party, he needed to submit 105.000 signatures of Russian citizens in support of his candidacy. He did so, but the CEC invalidated a signification part of them.

We explain how Russian election commissions use the signatures as a tool to eliminate undesirable candidates.

Read more … How voter signatures collection turned into an impassable barrier for the opposition

Statement. Russia has declared REM an ‘undesirable organization’

On 1 February 2024, the Russian Prosecutor General's Office declared the Russian Election Monitor a so-called ‘undesirable organization’.

Read more … Statement. Russia has declared REM an ‘undesirable organization’

Who is Boris Nadezhdin – the anti-war candidate for the Russian presidency?

Many are convinced that Nadezhdin's nomination is a well thought out plan orchestrated by the presidential administration. Even his surname has roots in the word "hope" in Russian.

Yet, these rumors have not prevented Nadezhdin from gaining almost unanimous support of Russian opposition and eventually becoming the only presidential hopeful with anti-war agenda.

Read more … Who is Boris Nadezhdin – the anti-war candidate for the Russian presidency?

Presidential elections 2024: Does the opposition have a chance?

REM asked a political analyst whether the opposition, both systemic and exiled, has a chance for success in the upcoming presidential election.

Read more … Presidential elections 2024: Does the opposition have a chance?

It’s the taking part that counts. What strategy will the opposition have for the presidential elections?

On January 14, representatives of Russian exiled opposition participated in a live broadcast on TV Rain to discuss their strategy for the upcoming elections in March 2024.

REM publishes a short summary of participants’ suggestions.

Election update V. Putin's presidential campaign has been rigged from the start

Russian CEC adopted regulations for candidates to run for the presidency. Predictably, not all applicants were able to obtain the status of a registered candidate. Meanwhile, the election campaign of incumbent President Vladimir Putin started with violations of electoral legislation.

In this review, we briefly recap the most significant events of late 2023 and early 2024.

Read more … Election update V. Putin's presidential campaign has been rigged from the start

Presidential elections 2024: Is there going to be a change in Russia?

REM asked a political analyst about socio-cultural differences between Russian regions and how they affect the voting results.

Read more … Presidential elections 2024: Is there going to be a change in Russia?

Dissent of the loyal: Women’s protest on the eve of the presidential campaign in Russia

After 600 days of genocidal war in Ukraine, dozens of women - mothers, wives and sisters - attempted to rally demanding the return of their loved ones home.

Any manifestation of dissent is an unlikely event these days in Russia due to the highly repressive environment and immediate crackdown on any instance of public discontent.

Read more … Dissent of the loyal: Women’s protest on the eve of the presidential campaign in Russia

How the Russian opposition is preparing for 2024 presidential elections

Vladimir Putin is to stand for a fifth term. Little doubt remains that Kremlin will make every effort to keep him in power.

Can the upcoming vote become a window of opportunity for a democratic regime change?

Here we explain how the quite fragmented Russian opposition intends to act in the presidential elections 2024 and what it recommends to the voters.

Read more … How the Russian opposition is preparing for 2024 presidential elections

Election update IV. Russia's presidential campaign is gathering pace

In this report, we recount the most significant November 2023 developments related to the presidential elections 2024.

Among them are Putin's presidential bid, test of e-voting, amendments to legislation on presidential elections and political “cleansings” in Russian regions.

The report is based on a regular news digest by the Golos Movement for Defense of Voters' Rights.

Read more … Election update IV. Russia's presidential campaign is gathering pace

Who is Ekaterina Duntsova – a candidate for the Russian presidency?

“Every day the life of ordinary Russians is becoming more difficult. Citizens cannot freely express their opinion if it does not coincide with the position of the authorities; the number of political prisoners is growing, hundreds of thousands of people have been forced out of the country. <...>

“Military operations” on the territory of neighboring states lead to imminent isolation and degradation”, her campaign website says.

Read more … Who is Ekaterina Duntsova – a candidate for the Russian presidency?

Russian presidential elections 2024: Is resistance at polls possible?

The election on 17 March 2024 will be the first presidential election during the war in recent Russian history. Further, it will be the first presidential election after the constitutional amendments 2020 that nullified the count of consecutive presidential terms and allowed Vladimir Putin to stay in power until 2036.

We asked an expert if there is any room for maneuver for opposition voters, given the unprecedented level of political constraints.

Read more … Russian presidential elections 2024: Is resistance at polls possible?

"We’ll have no time to celebrate the victory before the great lent"

In March 2024 election, Vladimir Putin should receive at least 80% of the votes with a turnout of 80%. According to “Verstka”, these are the benchmarks that the Kremlin's domestic policy bloc is setting for the Russian authorities.

The campaign slogan consists of three words: “Pride. Hope. Confidence”. The heroes of the “Special Military Operation” will also be invited to become Putin's confidants; however, the main focus won’t be set on them or on the war itself.

Read more … "We’ll have no time to celebrate the victory before the great lent"

Election update III. The presidential campaign in Russia has started

In this one-pager, REM recounts the most significant October 2023 events signaling the start of the campaign.

The text is based on an analytical report prepared by experts and published on the Golos Movement for Defense of Voters' Rights website.

Read more … Election update III. The presidential campaign in Russia has started

The first post-Putin elections: What they might look like

How to organize a fair voting system in post-Putin Russia? How elections should be arranged and who should be responsible for this? What principles of representation should be taken into account?

Political scientist Grigory Golosov discusses these and other questions in this article.

Read more … The first post-Putin elections: What they might look like

Opposition coalition: A good thing or “To hell with it”?

On 25 September, supporters of Alexei Navalny published a large text in which he rejected a coalition with the rest of the opposition. On the same day, Maxim Katz released a video where he disagreed with Navalny and called on “dissenters” to unite before the presidential elections in 2024.

In this article, political scientist Grigory Golosov explains which of the two strategies is more effective, and whether political coalitions in modern Russia make any sense at all.

Read more … Opposition coalition: A good thing or “To hell with it”?

Free elections post-Putin: Not a cure-all

The demand for free elections should be an indisputable cornerstone of any democratic reform program. That is why it is a common belief that the first order of business after the fall of the current regime in Russia should be to conduct free nationwide elections.

Political scientist Grigory Golosov argues that despite the importance of elections, this issue should not be the first on the agenda and explains why.

Online elections in Russia. What to expect from them?

Over the span of several election cycles, e-voting in Russia has proved to be a black box serving the regime’s needs.

After its launch in just a handful of regions, it is now expected to become available to all Russians in the 2024 presidential elections to facilitate fraud and deliver an overwhelming vote share for Vladimir Putin.

Read more … Online elections in Russia. What to expect from them?

Three politicians who opposed the war and won the elections

After the Russian invasion of Ukraine, most deputies who openly disagreed with Putin's war were sent to pre-trial detention centers or 'squeezed out' of the country.

However, despite the total suppression of the freedom of speech and assembly, there are still municipal politicians in Russia who openly oppose the war and win local elections.

We share the stories of three such heroes.

Read more … Three politicians who opposed the war and won the elections

Putin’s electoral theatre: Past, present and future

On 8-10 September 2023, Russia held local elections in two dozen different regions. The Kremlin could have easily canceled them by declaring martial law. Instead, elections were held in the newly occupied areas of Ukraine despite martial law. This suggests that Putin’s regime still finds sham elections useful.

This essay provides a brief history of elections in post-Soviet Russia, exploring the latest example of the Kremlin’s sham democracy and sketches the prospects of political changes.

Read more … Putin’s electoral theatre: Past, present and future

Elections without change?

Do observers in Russia possess the tools to maintain independent oversight of elections? How has the war influenced the pre-election campaign? Can the recent vote even be described as an election? What is the Russian government's motive for holding such “elections”, and what might we anticipate from the 2024 presidential campaign?

To find out, read this interview with experts.

Elections 2023 appear even less free and fair than before

8-10 September in Russia were days of elections of State Duma deputies in four districts, heads of 21 regions, deputies of 16 regional parliaments, 12 city councils of regional capitals, as well as elections in the occupied territories and numerous local elections.

REM summarizes the main conclusions from the observation.

Read more … Elections 2023 appear even less free and fair than before

What are the opportunities for the opposition in Russian elections?

The electoral and civil rights legislation in Russia is getting stricter year by year, leaving very little room for oppositional politics. What can opponents of the regime achieve in the face of constantly introduced obstacles?

In this article, we reflect on whether there is any room left for opposition politicians in Russia, and if it makes sense for them to participate in elections at all.

Read more … What are the opportunities for the opposition in Russian elections?

Spoilers and doppelgängers in Russian elections

The practice of nominating namesake candidates or similar-looking candidates is widely used in Russian elections.

In this article, we explain how this electoral technology works to mislead the voter and pull votes away from the opposition.

What are the specifics of Russian parliamentarism?

Do elections have any value in a country with strong repressive machinery where any politician whom the authorities may consider dangerous can be placed in jail?

The author of this article is convinced that elections in Russia present not only a high-cost ritual spectacle simulating democracy but also largely shape the interaction between the state and society.

Keep reading to find out more.

Read more … What are the specifics of Russian parliamentarism?

We are observing a decline in the willingness of parties to participate in elections

Parties are reluctant to participate in elections to regional and municipal assemblies, an expert report concludes. They understand the impossibility of fair competition and do not want to invest effort in fighting the ruling party. Further, the elections in the occupied territories cannot be considered legitimate either legally or procedurally.

Read more about the results of the nomination of candidates for deputies of local and regional parliaments.

Read more … We are observing a decline in the willingness of parties to participate in elections

‘Golos’ summarized the nomination of candidates for the 2023 gubernatorial elections

The report’s primary conclusion aligns with expert forecasts: genuine competition between candidates is anticipated in only one region, the Republic of Khakassia, out of the 21 regions that participate in the September elections.

Read this report summary for more statistics and expert insights.

Read more … ‘Golos’ summarized the nomination of candidates for the 2023 gubernatorial elections

A slow death of municipal autonomy in Russia

This article delves into the process of elimination of municipal autonomy from the 2010s to the present, leading us through a series of reforms that have helped Kremlin build the so-called ‘power vertical’.

A gradual transition from weak, but somewhat independent local governance toward loyal local appointees contributes to our understanding of how political decision-making works in high-capacity authoritarian states like Russia.

If there is Putin, there are no debates

This year, Khakassia emerged as the sole Russian region where its governor, communist Valentin Konovalov, invited his adversary, Sergey Sokol from United Russia, to a debate. While the audience hoped for a substantive political exchange, the discourse was dominated by accusations of mudslinging and chasing hype.

This article explores how debates in modern Russia have changed, why gubernatorial candidates avoid open discussions with opponents, and what the future holds for debates.

Why the war did not become the main topic of the election campaign

In the past, parties and candidates would offer distinct promises to voters, address social concerns, and even position themselves against the government. However, the current campaigns appear lackluster and devoid of a clear message. Even the topic of war is scarcely touched upon by the primary candidates.

This REM review explores why the war in Ukraine hasn't emerged as the predominant topic of the recent election campaign.

Read more … Why the war did not become the main topic of the election campaign

United Russia dominates district electoral commissions, where most electoral fraud originates

A recently published "Golos" report details who holds control over the precinct electoral commissions across Russian regions. REM provides insights into the key findings of the report, emphasizing its significance as we approach the 2023 elections and the 2024 presidential elections.

Voting under bullets and shells

Holding elections in the occupied territories of Ukraine on 8-10 September is a daunting task for the Russian authorities.

This long read explores how the ongoing military actions affect election preparations and how the Kremlin is making sure that there are no surprises.

Co-chair of Russian election watchdog Golos detained ahead of elections

Mass searches and interrogations of Golos activists took place across the country. What do we know about that by now?

Read more … Co-chair of Russian election watchdog Golos detained ahead of elections

Election update II. Legislative changes make it easier for "United Russia" to win elections

On the eve of the elections, Russian authorities adopted a new package of amendments to the electoral legislation. The changes aim to help candidates from the ruling party win in the September elections.

"The current government is not going anywhere". On political changes in Russia

Wagner's rebellion showed how weak President Putin's support base is. However, no real political changes followed. Are they even possible in modern Russia, and could elections - an instrument specially invented by the democratic world for this purpose - contribute to the changes?

Read more … "The current government is not going anywhere". On political changes in Russia

The Just Russia party distances itself from regional elections following the Wagner mutiny

News on Just Russia's withdrawal of electoral activity in the regions began to emerge shortly after Prigozhin's uprising in June 2023. Expert opinions differ: some believe it signals the falling from favor for the systemic opposition, while others argue that the party uses the uprising as a rhetorical cover-up for the internal splits.

Election update I. There will be no competition in the Russian gubernatorial elections 2023

In light of the gubernatorial elections to be held in September in 21 Russian regions, we analyze a report on the candidates running for governor. The report concludes that no real competition can be expected in these elections, with few exceptions.

Approval ratings do not predict change or Why we should stop gazing at political polls from Russia

Prigozhin's failed mutiny on June 24th sparked various speculations concerning his support among the Russian population.

In times of political turbulence, approval ratings become subject to interpretations fueled by the hope of regime collapse. An expert explains why putting so much trust in politicians’ approval ratings originating from today’s Russia might be delusional.

Playing heroes

All the proclamations about the active involvement of 'war veterans' in politics remain empty rhetoric.

In reality, the 'defenders of Donbass' hat is now worn by the same politicians who have held official positions for years. This verbiage and masquerade are designed not to please the voters but to satisfy one particular person.

The thing

As it turned out at legal proceedings held on the 9th of March, proving the illegality and inadequacy of the online voting system used in Moscow's elections in 2022 wasn't rocket science or high mathematics. On the contrary, it was as easy as asking for a certificate!

Moscow's i-voting system is not lawfully certified and contradicts legal requirements, court investigations revealed.

The martial electoral law

Again and again, the Duma adjusts electoral legislation to suit its current needs. This time the main innovation appears to be a "remote election" regime for the occupied territories. This squaring of the circle would allow martial law to stay and elections to be held concurrently.

Transcending 'unlimited potential for fraud'

For years, Moscow has been a hard place to win for pro-governmental candidates. Even online voting was hardly enough to secure trouble-free victories because the citizens used the traditional method. For the mayoral campaign of 2023, a new device is invented. 40% of precinct polling stations will evaporate into the Cloud.

How to sell Putin for the fifth time

The new marketing plan for selling Putin to the voter is being developed at the Kremlin in secretive "closed seminars". The new packaging for the quarter-century-old merchandise is being tested.

But the campaign's outcome will be decided on the battlefields, not, for the first time in this century, in the Kremlin's cabinets.

On the death of the Wizard

It's hard to believe that Russian elections, nowadays a synonym of rigging, falsifications and coercion, were almost honest before this man entered the post of the chief electoral officer.

Last week, Churov, also known as the Wizard, passed away, but his malevolent curses will haunt Russian elections for years.

First elections after mobilisation

Last year the Kremlin cheated people who came to pollings station. The regime said nothing about the upcoming draft. But merely within 10 days after the polling stations were closed, the recruiting centres were unexpectedly open.

It is not possible to repeat that trick again.

The doomed Code

The Communist Party prepared their Electoral Code for consideration by the Duma. They urge to make the third Sunday in March the primary voting day, eliminate multi-day and distant electronic voting, abolish voting in streets, etc.

Arkady Lyubarev, an electoral expert, shares the secret: Why the Duma will not enact any Code, even an immaculate one.

Monitoring of the Monitors

Ordinary non-public citizens of Russia become threat number two once they acquire knowledge related to the electoral field and touch the sphere where one of the fundamental myths of the regime is created: the myth of nationwide popular support.

Slippery AstroTurf of the Kremlin war

A new study of Russian social media proved half of the sabre-rattling messages to be artificial duplicates orchestrated from the single centre. The research has also revealed prolific pro-governmental professional bloggers trying to dominate the Russian Internet community. And yet, they are 1.5 less popular than anti-war authors.

E-voting: invisible for observers, invincible for lawyers

The distant electronic voting keeps pushing the limits of our imagination. After the actual process of voting, where the entire process took place outside the view of key participants, came the legal revelation of how the lawmakers preemptively absolved themselves and the Central Election Commission of any responsibility.

Read more … E-voting: invisible for observers, invincible for lawyers

Outstanding resilience to repression and loyalty to democracy

Over 10 years, EPDE has evolved into a professional network of 16 members from Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Germany, Hungary, Lithuania, Moldova, Norway, Poland, Sweden and Ukraine. EPDE is united in the common goal of improving democratic election processes across Europe and providing a platform for peer learning and professionalisation for its members and experts.

Read more … Outstanding resilience to repression and loyalty to democracy

Il Duce served a la Russe

The Russian people have not named Vladimir Putin Il Duce (‘The Leader’). He has been identified as such, just as earlier in history in Italy, by the elite. And as in Italy, the elimination of fascism can only be finalised by integrating the ex-fascist country into the Western world.

Unprecedentedly explicit: election observers are human right defenders!

The United Nations Special Rapporteurs on the situation of human rights defenders and on the right to freedom and peaceful assembly and of associations issued a statement on 27 October 2022 explicitly recognising citizen and international election observers as human rights defenders.

Read more … Unprecedentedly explicit: election observers are human right defenders!

The Emperor's secondhand clothes

By going to war in Ukraine, the Putin regime tried to be what it pretended to be, but its facade crashed into reality. Any myth is effective as long as its creator does not allow it to clash with reality. Skilled myth-makers know this well and guard their creations, and they do not, of course, believe in their own myths. Putin observed these rules for a long time, but he gradually began to believe in the myths that he and his entourage created and then acted in accordance with them.

Those who dared - II

We continue to acquaint our readers with those rare, brave individuals who challenged the Putin regime at home during elections in September 2022, when the regime began to receive the first sobering blows at the front in Ukraine.

What happened with the reckless candidates after the elections? How did they survive the ordeal? Who managed to stay, and who had to flee the country? You will learn it in the following, the final part of this coverage, which is currently being written exclusively for REM.

Serfs of the State

Today we will discuss budgetary workers and their role in Putin's regime. Who are the "budgetniki"? Are they the backbone of Putin's regime? In what countries and under what conditions are elections susceptible to manipulation through budgetary workers?

Those who dared

On 12 September 2022, President Zelensky announced the liberation of 6,000 km2 in a massive counter-offensive. For President Putin, the day was the beginning of a period of humiliating defeats, of the disgraceful retreat of his army and a chaotic attempt at mobilisation.

But up to this very day, there had been an election campaign in Russia. In the choking atmosphere of "special military operation", under censorship and repression for any word of dissent, there were amazing people who dared to challenge the System.

EPDE statement on house searches of Russian election observers

EPDE strongly condemns this act of repression, intimidation, and unlawful interference into citizens' constitutional right to free elections

Read more … EPDE statement on house searches of Russian election observers

It is impossible to establish the genuine will of the voters, says Golos

The election outcomes were achieved in unfree, unequal election campaigns, in an environment of restrictions on the right to be elected for a substantial number of citizens and on fundamental political rights. Under such conditions, it is impossible to establish the actual will of the voters.

Read more … It is impossible to establish the genuine will of the voters, says Golos

The third voting day in the express overview by the Russian nonpartisan election monitor Golos

By the end of voting, tension at the polling stations was growing. The number of reports claiming that commission members, police and unauthorised persons put psychological pressure on observers has also increased.

The second voting day in the express overview by the Russian nonpartisan election monitor Golos

According to Golos Movement, the main trends for the second voting day were conflicts between members of commissions and civic observers, signs of possible falsifications, and bribery and coercion of voters.

The first voting day in the express overview of the Russian nonpartisan election monitor Golos

Main election day trends: pressure on election observers and candidates, bloated turnout in Distance E-Voting, coerced voting, failure of the Electronic Voter Register, violation of the rights of election committee members, observers and mass media, fabrication of fakes and attempts to discredit citizen observers.

The 2022 elections as the last refuge of the scoundrel

Without the successes in Ukraine or on the propagandistic internal front, these elections are the last opportunity for the Kremlin to assert the concept of business-as-usual, to ensure the grip on regional assemblies. It is vital in the anticipation of an economic slump, Moreover, the new municipal structure needs a strong hand. Finally, it is a testing ground for “distant voting”, impermeable for observers.

Read more … The 2022 elections as the last refuge of the scoundrel

The ruling Russian Party of Dead Souls

This investigation is both a quantum leap in electoral observation and the most severe blow to the ruling party's reputation. As you’ll see, the findings even question who is the genuine ruling party in Russia. It was such a severe blow that Ms Pamfiliva, the chairwoman of the Russian Central Election Commission, personally reported the case to President Putin within a week of the publication.

Putin’s Second Front: no peace for the wicked

The failure of the PR campaign uncanny resembles the collapse of the military campaign on the battlefields. A new media monitoring report on "special operation" describes the unexpected resistance of the Russian population to a heavy propagandistic barrage.

No European politicians to whitewash Kremlin’s fraudulent elections or pseudo-referenda

EPDE calls on all national and regional Parliaments of the EU, the European Parliament, the PACE and the OSCE (OSCEPA) to undertake measures preventing their members from participating in illegitimate “election observation”, organized to whitewash illegal electoral processes.

Read more … No European politicians to whitewash Kremlin’s fraudulent elections or pseudo-referenda

Wartime elections

The upcoming E-day in Russia: deprived of the freedom of speech and party lists, elections are still the only way to grasp the citizens' attitude towards authorities.

Elections "in accordance with the plan"

Final part of electral fraud revelations made by the former vice-mayor of a millionaire Russian city.

Elections in a close order formation

Essential changes to Russia’s electoral legislation were introduced after its aggression against Ukraine. Indeed, one might discern some military flavour in these adjustments: discipline, unification, centralisation, monopolisation of chain of command, and elimination of tools of civil control. Dr Arkady Lyubarev, candidate of legal sciences, co-author of federal and Moscow electoral legislation, and editor in chief of the draft Electoral Code, gives his assessment of the further deterioration of the electoral system in Russia.

The nine aggrieved elects

This story is quite exceptional. We’ve never heard the testimony of electoral fraud from a witness of such high administrative rank and political status: the former vice-mayor of a millionaire city, a former head of administration of a district, a member of the regional Political Council of the United Russia Party, ruling political organisation in the country, the Secretary of the district Political Council of the party and finally, a former KGB and FSB officer. Quite an informant!

One must prepare for negative consequences – OPORA

The invaders have not been consistent in governing the temporarily occupied territories. L/DPR militants ‘appoint’ nonames to nonexistent offices in some places. In others, there are talks of holding a pseudo-referendum, and PR campaigns are run elsewhere to an incorporation in the occupied Crimea. The ‘people’s republic’ format will not work this time. However, it is still worth preparing for a negative scenario.

Read more … One must prepare for negative consequences – OPORA

To Russian opposition after the disaster of 2022: Enlighten, not repent

A. Kynev: All these hand-wringing and pathetic calls to each end everybody to repent is the utter public suicide of the opposition and a priceless gift to the government. No one has ever come to power or won an election on the pretext of humbling themselves and repenting. Therefore, this approach is an absolute dead-end and insane endeavour, at least from the electoral point of view.

Read more … To Russian opposition after the disaster of 2022: Enlighten, not repent

Elections during Russia’s ‘Special operation’

The Russian authorities keep emasculating the institution of elections and modelling it after the Belarusian version. Notably, these changes do not match too well with the allegedly increased popular support for the Russian authorities against the backdrop of the war. Instead, it demonstrates a lack of confidence that the autumn elections will go smoothly.

From election observers to ‘foreign agents’: how voters' rights defenders of the ‘Golos’ Movement are persecuted

Since September 2021, twenty regional coordinators and experts of the 'Golos' Movement in Defense of Voters' Rights were added to the registry of foreign media outlets performing the functions of 'a foreign agent'. Here's an overview of how election observers are being targeted and persecuted.

The League of Voters appeals to the ECHR

The 'League of Voters' Foundation appealed to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) for an interim measure requiring the Russian authorities not to liquidate it pending the ECHR proceedings on its earlier complaint. Should the liquidation proceed, it would make all future legal activities of the Foundation impossible: the organization would be unable to rent office space, collect donations, will lose all of its property, and would be forced to cease its human rights and educational activities.

Internet voting and shortage of candidates: how 2022 Moscow municipal elections will be held

On September 11, 2022, municipal elections will be held in 125 of Moscow's 146 districts. It is not yet known whether these elections will be a multi-day process, but it is already certain that online voting will be used again and that parties that are preparing for the elections are already facing candidate shortages. Yekaterina Grobman reviews the current situation and what we can expect in 2022.

‘Fortress’ Plan

Stanislav Andreychuk on how the Kremlin is changing laws that regulate Russia’s polity and elections to maintain the status quo.

Questionable credentials of the Russian Delegation to PACE after flawed Duma elections 2021

Independent election experts have described the 2021 Duma elections as the dirtiest elections in Russia's history. The lack of public control, the deprivation of millions of Russian citizens of their passive suffrage, massive manipulation of results through e-voting, holding of elections on the annexed territory of Crimea, and the inclusion of voters from the occupied Eastern Ukraine put the legitimacy of the current State Duma and the new PACE delegation under question.

2021 Results. Laws of the year

The passing year built on legislative trends of the previous one and even brought about many innovations in censorship, limitations of online activities, and infringements on privacy. Such provisions include multiple prohibitions related to the Great Patriotic War, the ‘law against Anti-Corruption Foundation’, and infamous QR codes.

On the liquidation of International Memorial

On 28 December 2021 Russia's Supreme Court ruled to close International Memorial. The lawsuit, filed by the Prosecutor General's Office, referred to a missing 'foreign agent' designation on some of the materials produced by International Memorial. This is only a formal pretext, though, and the court hearings showed that these allegations were groundless.

Things Will Not Be The Same: OVD-Info on the Liquidation of Memorial NGOs

OVD-Info's statement on the liquidation of its partner - the 'Memorial' Human Rights Center.

Read more … Things Will Not Be The Same: OVD-Info on the Liquidation of Memorial NGOs

Departed Russia of the Future

Hardly any of Navalny's key allies currently remain in Russia. The Insider interviewed former coordinators of Navalny's regional headquarters to find out why and how they left, what they do in exile, and under what conditions they are willing to return to Russia.

Russia is liquidating the League of Voters

On December 8, the Basmanny District Court of Moscow ruled to liquidate the 'League of Voters' Foundation. Its leaders believe that the ruling is politically motivated and is aimed to destroy the organization which is a partner in the 'Golos' Movement and supports the training of independent citizen election observers in Russia.

Created and (or) distributed: Discriminatory aspects of the application of legislation on ‘foreign agents’

OVD-Info reviews the newly expanded 'foreign agents' law to identify and analyze discriminatory aspects of the legislation and its application.

Undercover: How observers are trained at the Civic Chamber of Moscow

A member of the 'Golos' Movement for the Defense of Voters' Rights recounts their experience observing elections on behalf of the Moscow Civic Chamber. According to the activist, the institution appears to purposefully instruct observers in such a manner as to limit their ability to make a real difference at the polling stations.

Read more … Undercover: How observers are trained at the Civic Chamber of Moscow

The Party's gold. How United Russia misappropriates Russian Railways’ money under the guise of "donations"

Last year United Russia collected a record amount of donations from legal entities, 4.8 billion rubles. The Insider learned that the party received about half of this money from major Russian Railways contractors, some of which seemingly could not afford to make such "donations". Despite claiming to channel funds towards charity and fighting the Coronavirus, the party spent it on the maintenance of its apparatus and election campaigning.

‘Golos‘ Movement supports Memorial and calls for an emergency civic meeting

Russian authorities have moved to liquidate the International Historical Educational Charitable and Human Rights Society 'Memorial' and its affiliate, Russian Human Rights Centre 'Memorial'. The 'Golos' Movement calls for solidarity with Russia's longest-standing human rights organization.

Read more … ‘Golos‘ Movement supports Memorial and calls for an emergency civic meeting

Elections, totalitarian style

The political bloc of the Moscow Mayor's office has begun campaign preparations for the 2022 municipal elections. Meduza breaks down the key points in the preliminary campaign plan here.

Golos' statement on the online voting in Russian elections

Following the observation of the September 19, 2021 elections, the 'Golos' Movement stated that 'the current electronic voting system does not meet the high standards of public accountability of electoral procedures', which the Russian Constitution and legislation establish as mandatory. Despite this position, some promoters of online voting in Russia have been claiming otherwise.

Read more … Golos' statement on the online voting in Russian elections

Election Day-2021 in Bashkiria: 'Put in the target number I set'

Preliminarily evaluating the elections to the Ufa City Council and the State Duma in the Republic of Bashkortostan, the 'Golos' Movement regretfully cannot recognize the elections as truly fair, i.e., fully compliant with the Constitution, the laws of the Russian Federation, the laws of the Republic of Bashkortostan, and international election standards.

Read more … Election Day-2021 in Bashkiria: 'Put in the target number I set'

Statistical analysis of elections in Kuban

According to the analysis by Sergey Shpilkin, 889 thousand out of 1.7 million votes for United Russia in Kuban do not fall into the normal mathematical distribution. This can result from direct falsifications, pressurized voting of the employees of state-owned enterprises, public institutions, and local authorities, and the use of an administrative resource.

When they came for the Communist Party: Arrests, sieges, and pressure on supporters after the State Duma elections

The Communist Party received 19% of the votes in the last elections to the State Duma. After that, the party's supporters faced unprecedented pressure for the 'systemic opposition.' They were detained, fined, sentenced to administrative arrests, and blocked in the party premises. CPRF continues to challenge the election results and demand an investigation by the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

Hot potato: Nearly a fifth of Russia’s new State Duma deputies owe their jobs to secondhand mandates

On Tuesday, October 12, the new convocation of Russia's State Duma convened for its first session. Roughly a fifth of all lawmakers — 88 of 450 deputies — received their seats from higher-ranked candidates on party lists, winning the jobs because others didn't want them.

'Golos' Movement: It won't be easy, but we can do it

Statement of the 'Movement in Defense of Voters' Rights "Golos"' on inclusion of its members into the Foreign Agents Registry, October 5, 2021.

Read more … 'Golos' Movement: It won't be easy, but we can do it

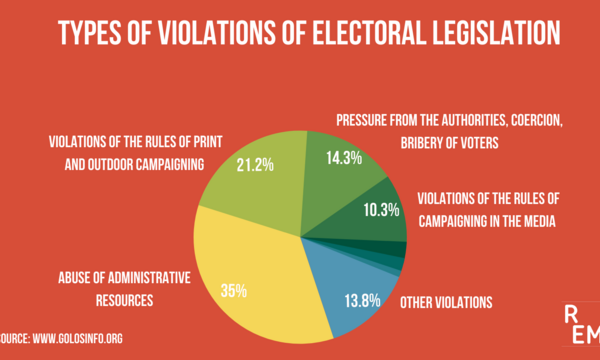

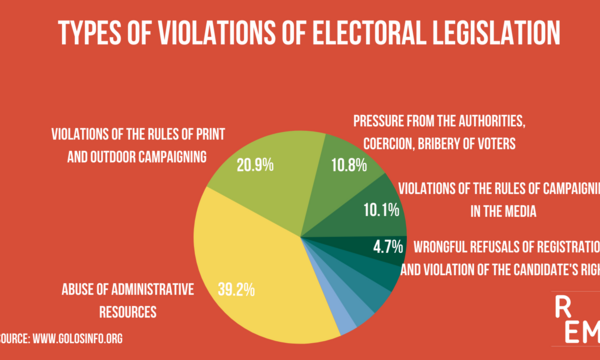

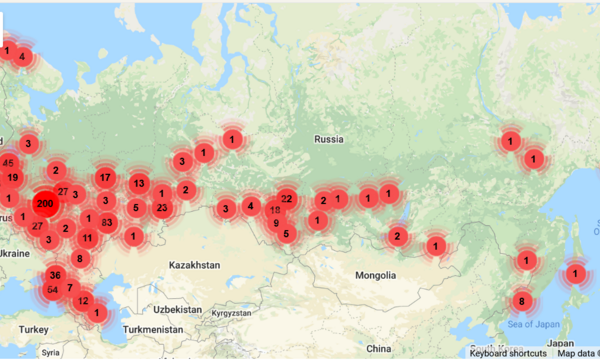

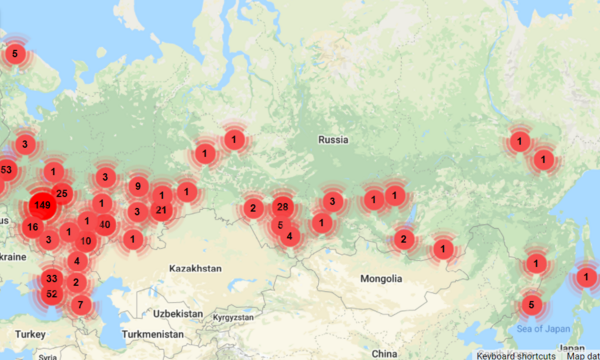

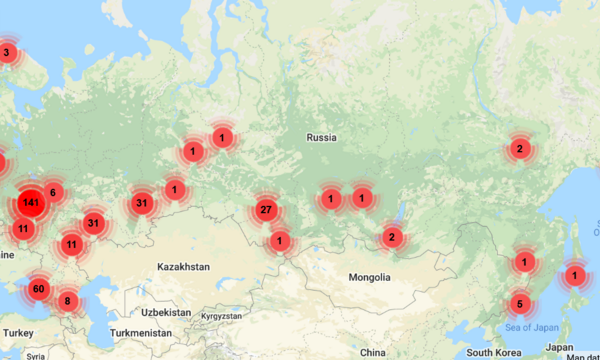

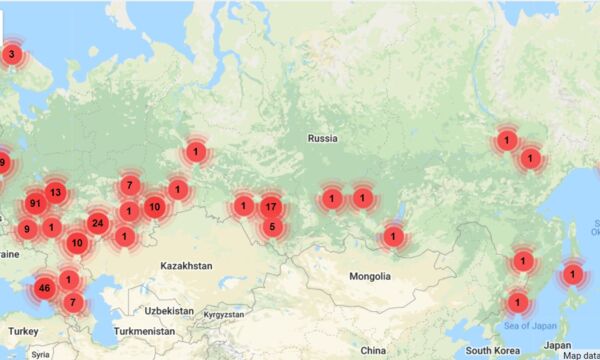

Map of violations: three record-setting days

In total, from the beginning of voting dated September 17, 'Map of Violations' by the 'Movement in Defense of Voters' Rights "Golos"' published 4592 reports. The Map is a project that collects information about possible electoral violations using the principle of crowdsourcing – observers, voters, members of commissions may report alleged violations witnessed during the electoral campaigning or voting using a submission form on the website or a telephone hotline.

First Findings of the Moscow's Remote Electronic Voting Technical Audit

The "remote electronic voting" or online voting held in the Russian capital during the September 17-19, 2021 elections was scandalous, to say the least. In response, two groups have been formed by the Russian public to scrutinize the results.

Read more … First Findings of the Moscow's Remote Electronic Voting Technical Audit

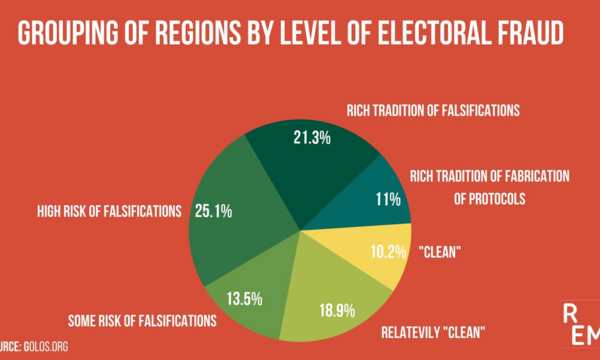

Levels of electoral fraud in the Russian regions

In order to help assess the outcomes of 2021 State Duma elections, the 'Movement in the Defense of Voters' Rights "Golos"' provides a reference analysis, dividing Russian regions into six groups based on the level of falsifications in the federal elections of 2016 and 2018 and in the all-Russian voting in 2020.

Read more … Levels of electoral fraud in the Russian regions

Remote electronic voting: results cannot be verified

A scandal in the capital: lengthy vote tabulation, a radical overhaul of the whole election results, and shut down of the observers' node.

Read more … Remote electronic voting: results cannot be verified

2021 State Duma elections: first statistical estimates

Sergey Shpilkin analyzes data from 96,840 polling stations that cover 107.9 million registered voters out of 109.2 million on the list. His analysis demonstrates that at the polling stations where the results appear genuine, the turnout is on average 38% and the United Russia's share of votes is between 31% and 33%.

Read more … 2021 State Duma elections: first statistical estimates

Preliminary findings of observation of the September 19, 2021, State Duma elections

This is a preliminary statement on findings of observation on the main voting day, September 19, 2021, by the 'Movement in Defense of Voters' Rights "Golos".' Golos ran long-term and short-term observation of all stages of the campaign. In the course of the elections, the united call center's hotline received 5,943 calls. The 'Map of Violations' received 4,973 reports of alleged violations by noon 20 September, Moscow time, including 3,787 on the voting days.

Read more … Preliminary findings of observation of the September 19, 2021, State Duma elections

Voting Day II: A Brief Overview

This is a brief overview of election monitoring findings on the Second Voting Day, September 18, 2021 by citizen observers of the 'Movement in Defense of Voters' Rights "Golos"'.

Voting Day 1: A Brief Overview

This is a brief overview of election monitoring findings on the First Voting Day by citizen observers of the 'Movement in Defense of Voters' Rights "Golos"'.

The election campaign and administrative mobilization of voters in September 19, 2021 elections

The September 19, 2021 elections are marked by growing pressure on media and individual journalists, attempts at blocking information about "Smart Voting", and massive coercion of voters to vote and register for e-voting and mobile voting. In parallel, social media has been growing in importance for years as a space of more freedom and an alternative information channel. Here are the main findings of the report that focuses on the impact of these two antipodal trends.

'The three heroes': more than a third of social media mentions are related to United Russia, CPRF, and the New People party

This report covers the monitoring of social networks from the 10th to the 11th week of the election campaign (August 23 to September 5) to the Russian State Duma, scheduled for September 19, 2021.

Residents of Russia-Occupied East Ukrainian Territories Encouraged to Vote in 2021 State Duma Elections